Autumn Kayaking in the North Channel

I’ve been hopelessly addicted to paddling on Georgian Bay since I was a kid. If I’m not on the bay, you better believe I’m planning the next trip.

It started with day trips within the protected bays of Camp Hurontario, in cedar strip canoes. It’s since expanded to multi-day adventures in sea kayaks, smashing into waves on open water.

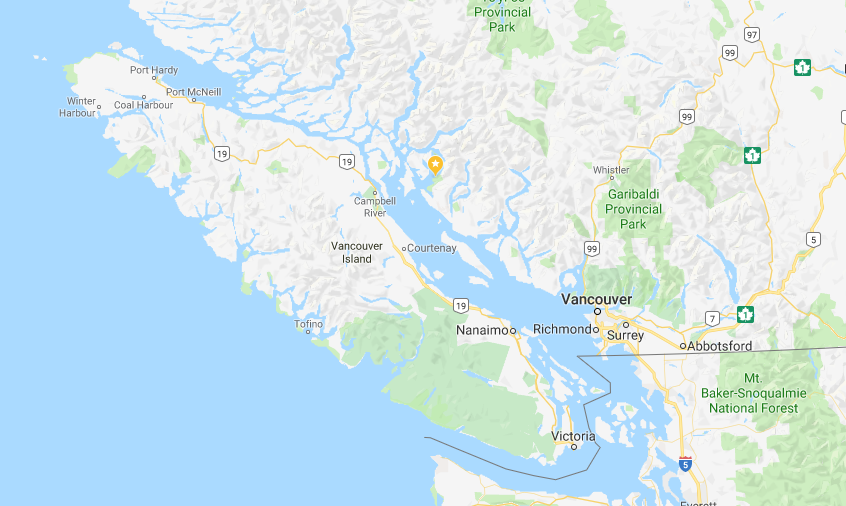

At this point I’ve meandered across most of the coast of the Thirty Thousand Islands, from Honey Harbour to Killarney, with few areas unexplored. One of the last stretches that stoked my curiosity was the North Channel.

Despite appearing to be beautiful territory for adventures, there’s very little information online about sea kayaking in the North Channel. Is it too exposed to explore? Too far from Toronto for traffic? Are people keeping it a secret? In October 2024, my brother and I decided to find out.

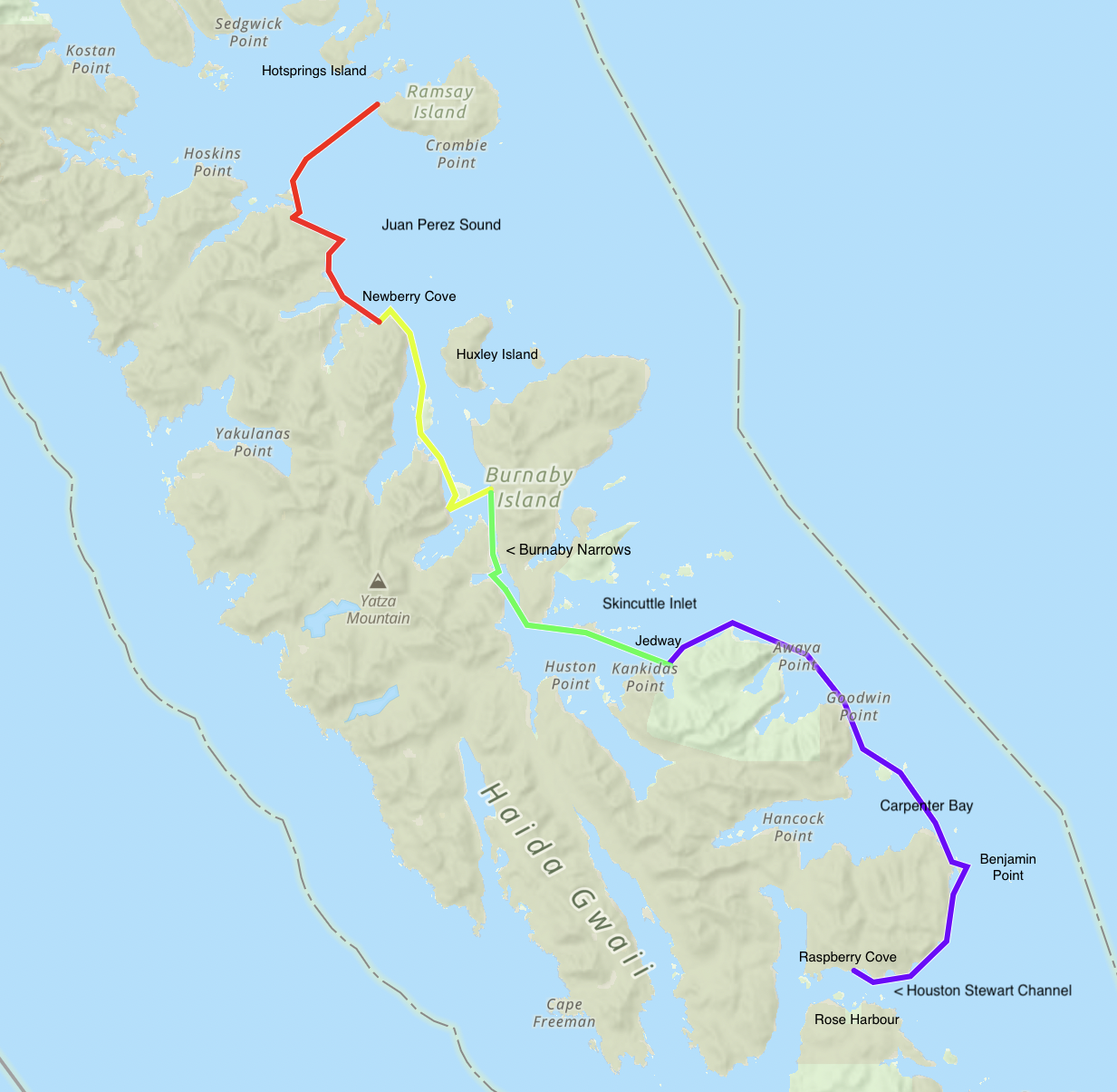

The Route

Until a few weeks ago, I knew very little about Georgian Bay’s North Channel other than that it exists, and you can see it on a map.

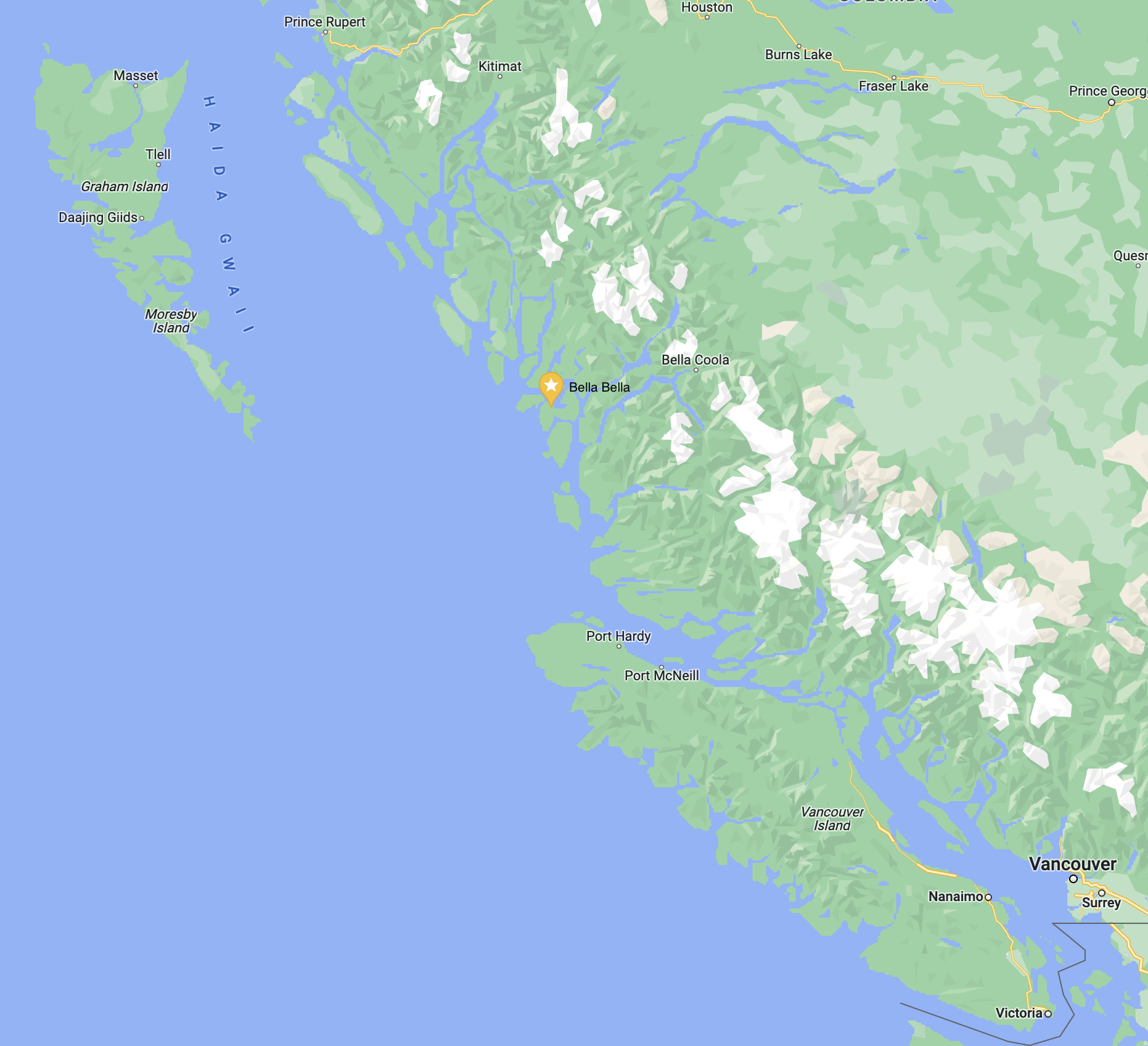

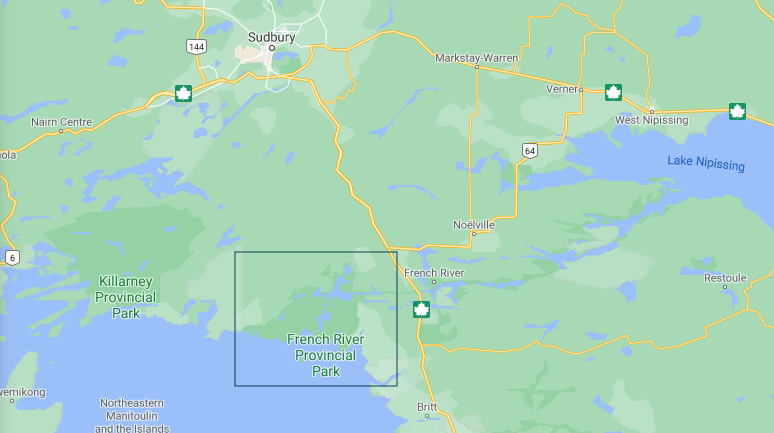

The North Channel sits above the world’s largest freshwater island (Manitoulin), below the LaCloche mountains, and runs over 150km east to west between Whitefish Falls and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. There are islands sprinkled along the northeastern shore, before the Channel turns to open water west of Algoma Mills. At its widest point, it’s over 30km across. To put that in perspective, it’s about 50% wider than the Queen Charlotte Strait in BC.

A billion-year old lava flow.

The geology of the North Channel is incredible. The Canadian Shield’s billion year old granite and gneiss bands meet the quartzite of the LaCloche range and crash against the limestone deposits that are so familiar along the Niagara Escarpment. We wanted to see it all.

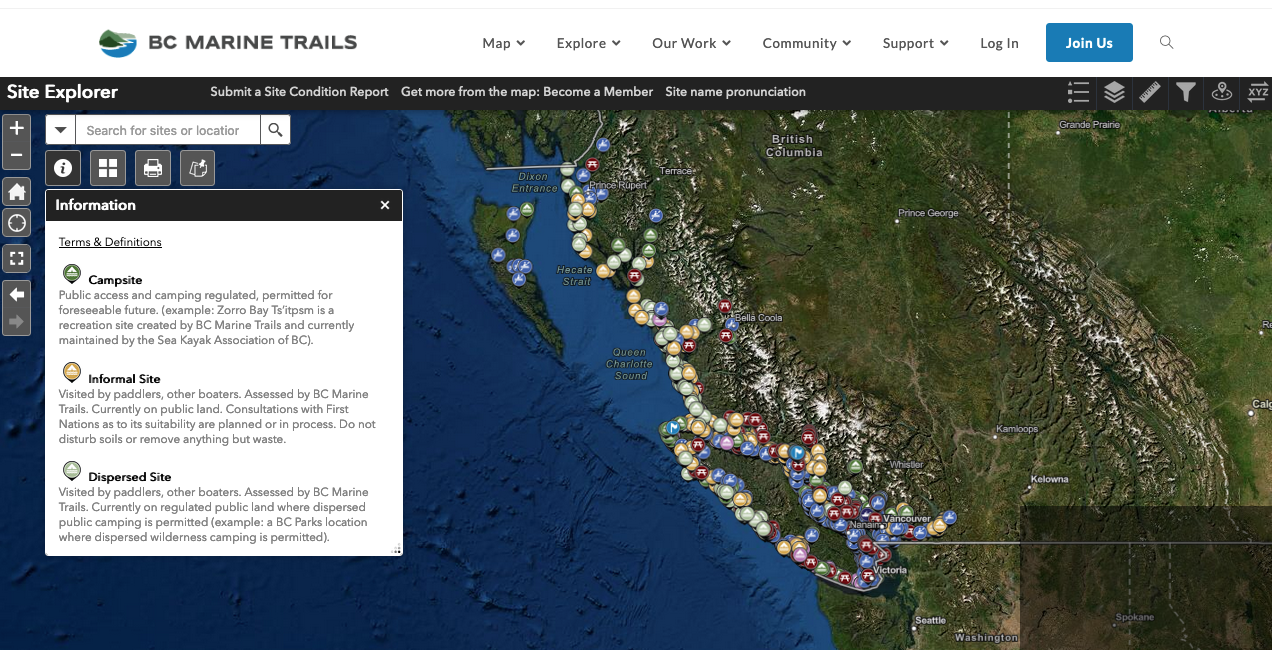

The majority of the route planning for this trip was done via Google Maps satellite view and the Crown Land Atlas. Much of this area has been tagged as a potential expansion for the LaCloche Provincial park, so it sits somewhere between crown land and park status and I couldn’t find any map publishers who had sites and trails in the area.

Instead, I used satellite views to look for familiar ‘shieldy’ type clearings that look campable, and compared them against the Atlas to make sure I wouldn’t end up on private land. Beyond enjoying a trip on the bay, I was keen to make a mental map of an unfamiliar area - finding campsites, routes, and scenery that would paint a picture for future expeditions.

Unlike the coast of Georgian Bay, the islands in the North Channel are fairly far apart. There aren’t many places to hide, and it doesn’t take much distance for the wind spirits to throw up a fuss and make inter-island travel dangerous if not impossible. We kept our route options open until the very last minute, glued to the weather reports, given that both air and water temperatures drop by the day this time of year.

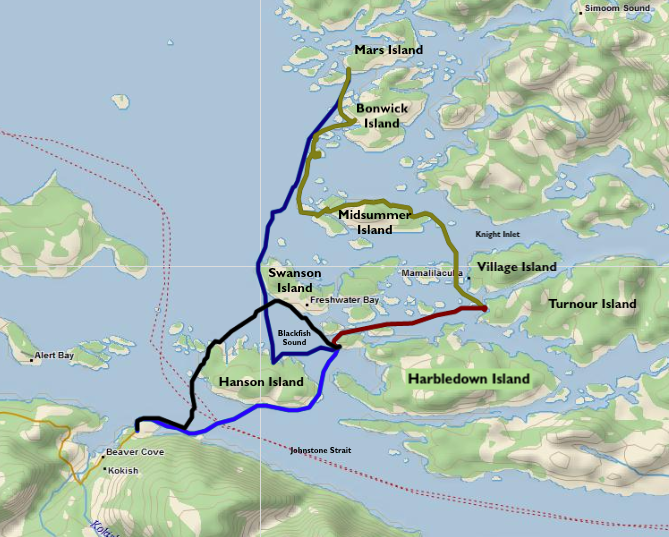

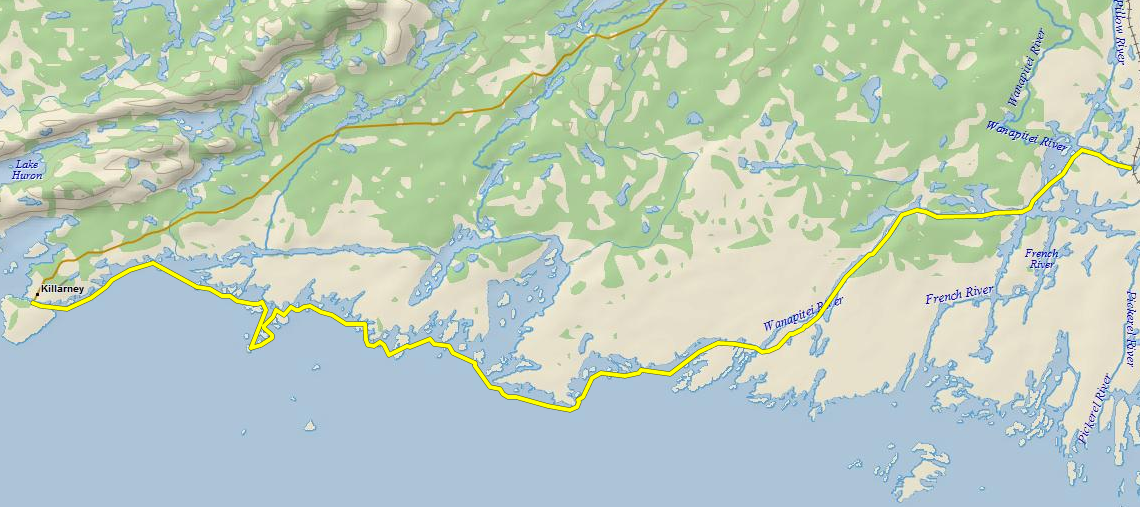

Our route from McBean Harbour, around Fox Island to Croker and the Benjamins. Download the GPX file here!

Thankfully, there are lots of options to launch kayaks up here: to the south, Little Current on Manitoulin Island; to the east, Whitefish Falls; and to the west, the town of Spanish. With heavy western winds on the forecast (as is tradition), we settled on launching along the north shore, at McBean Harbour, and venturing into a few of the central islands of the North Channel for a chill(y) long weekend.

The Trip

As with all of our adventures, this trip began with a long drive before getting to put our kayaks in the water. To cut some of the drive time, we opted to let the Chi-Cheemaun ferry usher us across to Manitoulin. 2024 marks the 50th Anniversary of the Chi-Cheemaun, and the ship was full of artifacts highlighting the rich history of ferry travel along the Great Lakes.

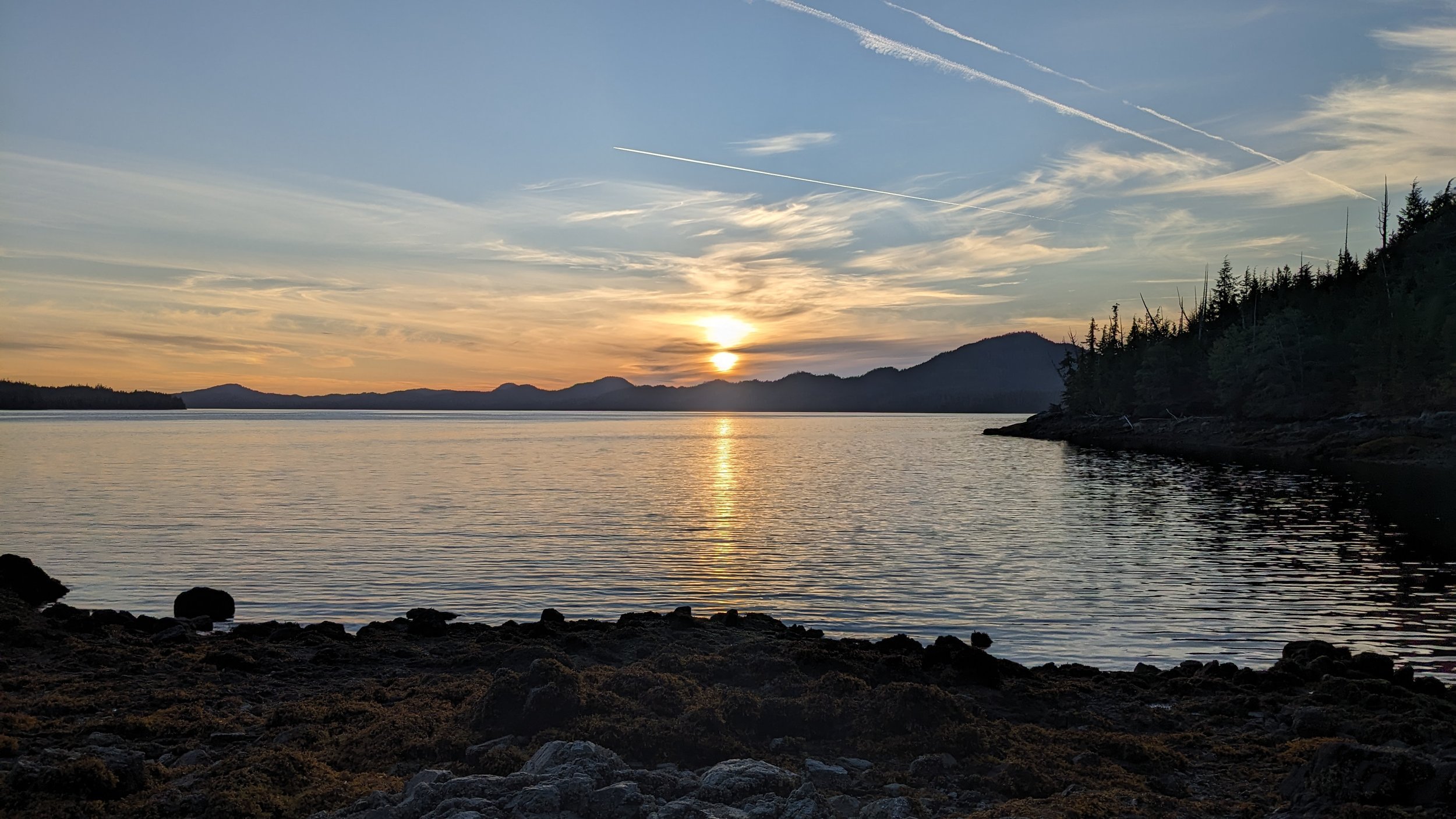

We soaked in the sunrise topside before landing in South Baymouth and finishing the last leg of our drive to McBean Harbour.

BC Ferries eat your heart out!

Wetsuits zipped, we packed up our gear and pushed off from the McBean Boat Launch. The launch was quiet, except for a few parked cars, but I imagine in the busy season there’s someone collecting cash for parking, and a bit of a wait at the small dock. Wrapping around the eastern tip of Fox Island, we fought wind and waves on the way to our first destination: the Benjamin Islands.

The Benjamin Islands stood out on satellite view as classic Georgian Bay shield-type islands with plenty of potential campsite options for us. Not to mention a protected cove to hide from the ceaseless western winds.

What I didn’t expect, though, was just how high some of these islands were off the water. This is Ontario! We don’t have altitude…

An extension of the LaCloche range, many of the surrounding islands and shoals had cliffs and hills that were over 100ft high. This made for beautiful views, but tricky landings.

We settled on the Benjamins as a basecamp to explore the area over the weekend. We’d identify sites, hike shorelines, and explore as far as we could within the boundaries of safety.

One of the many beautiful beaches on South Benjamin island.

On our second day, the winds calmed down and let us explore all the bays and inlets of South Benjamin Island at a leisurely pace. Centuries of pounding waves and mineral erosion from Manitoulin have formed beautiful sandy beaches between the cliffs. These little inlets offer protection from storms and almost all have a cozy site to tuck into, depending on the wind direction.

Tuning into our radio for regular weather reports, we planned a little excursion around Croker Island the following day, after a big storm had finished blowing through overnight.

Winds picking up on the trip back from Croker Island.

The jaunt across to Croker reminded us how exposed the paddling is around here. It was only a few kilometers across, but that’s more than enough throw distance for waves to pick up and challenge even experienced paddlers. We would look for, and track towards, any scattered shoals to offer us even a brief windbreak as we made our crossings.

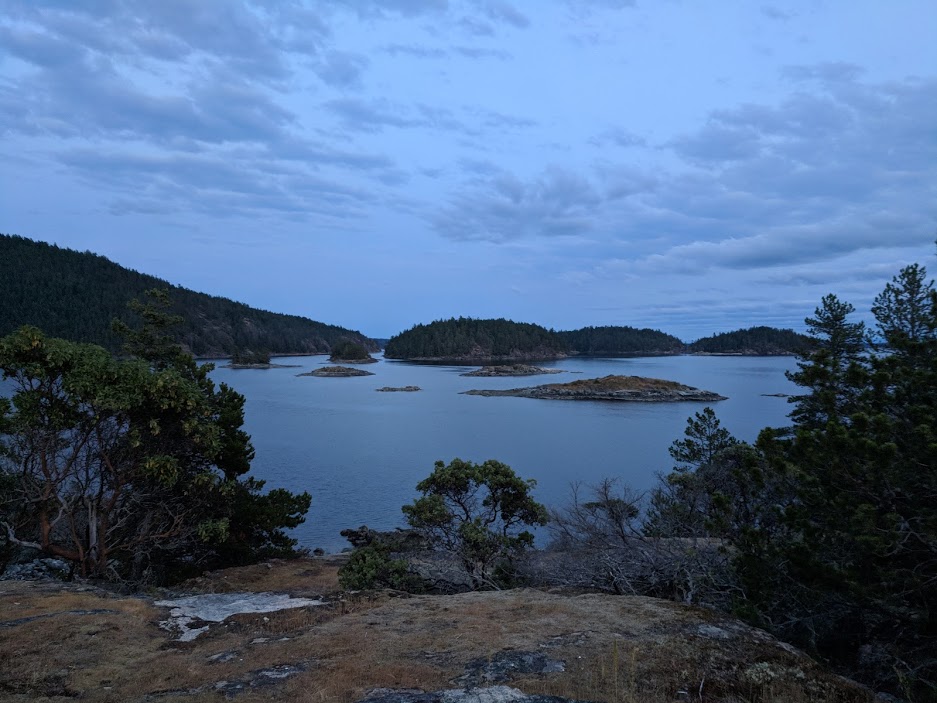

On our final night at South Benjamin, we decided to get some steps in and explore the island on foot. Every corner of the island is connected by exposed rocky sections that let you circumnavigate it without bushwhacking.

Apparently we weren’t the first people to explore on foot, because someone had ‘blazed’ a trail with pieces of yellow terrycloth tied to tree branches across the north-west coast. It was a blast to follow the winding trail up and down, between valleys and vistas, before returning to camp for a well-earned rest.

Looking back out towards Manitoulin Island from the ‘Terrycloth Trail’.

We left the Benjamins the following morning, making our way back around the north side of Fox Island to settle in closer to the harbour and give us a shorter final day. Wrongly assuming a tailwind would be more fun than a headwind, we were jostled and thrown along the channel by a northwest wind until we settled in at a quiet site facing back into McBean Harbour.

The weather mostly played in our favour over the weekend. Rain was sparse, winds were (fairly) manageable, and temperatures didn’t drop below freezing. For mid-October, I consider all of those a win.

A full rainbow after a brief storm to cap off the trip.

And so, here I am reflecting on the North Channel after a lifetime of not knowing it existed. Is it too exposed to explore? Certainly not, although you may need to be nimble with your routes given the distance between islands and the inbound weather. Too far from Toronto for traffic? It appears so, though the drive is barely longer than getting to Killarney or Algonquin.

Are people keeping it a secret? Absolutely yes. And now I know why.

Pro Tips

The North Channel is a combination of private, crown, reserve, and conservation land. Use all available public maps to form an opinion of the right places to go, and plug in potential routes to your mapping app of choice well ahead of time.

Stay flexible! Prevailing winds will usually be west to east, but that’s not always the case in this region. Long crossings can be dangerous so plan accordingly: radio, wetsuits, and optimize your route for windbreaks.

Use satellite views and contour lines to pick bays and inlets that might make great campsites, and leave yourself options. A few spots I thought would make great sites turned out to have impossible landings, or were too hilly to camp on.